An issue came up on one of the forums about which is the best book from which to learn about the Crowley-Harris Thoth deck. The answer for almost everyone is, without question, Aleister Crowley’s Book of Thoth. This, despite the fact that, for most beginners in esoteric studies, it seems impenetrable. Books by Duquette and Banzhaf are proposed as intermediaries and I agree they are excellent choices, but a problem occurs when Angeles Arrien’s name comes up. Her Tarot Handbook: practical applications of ancient visual symbols takes a completely different approach to the deck, which is often characterized as the “make up anything you want” variety—though it isn’t that at all. I should mention I took several classes with Angie on the Thoth deck starting in 1977, and so I’m not at all objective in my views.

Angie’s approach is based on Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious and the meaningful repetition of archetypal images and themes across world-wide human cultures. The statement by Arrien that probably infuriates people the most is: “I read Crowley’s book that went with this deck and decided that its esotericism in meaning hindered, rather than enhanced, the use of the visual portraitures that Lady Frieda Harris had executed.” Of key importance was that Arrien experienced a powerful response to the deck that did not arise from an esoteric OTO or Golden Dawn background. It was not specifically a rejection of Crowley, though it is easy to take it as such.

Instead, Arrien recognized most of the symbols from her study of anthropology and mythology. As a result she felt that “a humanistic and universal explanation of these symbols was needed so that the value of Tarot could be used in modern times as a reflective mirror of internal guidance which could be externally applied.” She believed that the Thoth deck symbols could be read in an other-than-esoteric way—specifically, as cross-cultural psychological symbols (archetypes from the collective unconscious). Her book offers this alternate perspective, based on the work of Carl Jung, Marie Louise von Franz, Joseph Campbell, Ralph Metzner, Mircea Eliade and Robert Bly.

In essence, Arrien asked: What do these symbols tell us if we strip away the esotericism and look at them purely as symbols and archetypes from the collective unconscious reflecting myths and images that have appeared across many cultures?

I see this simply as an alternate reading of the deck—not as a demand that we discount Crowley—but, rather, asking what can be seen if we do ignore Crowley? Is there anything else to this deck? Do real ‘true’ symbols transcend fixed definitions? Can they transcend any and all dogma?

We might also ask: If Crowley’s book were lost (along with all other esoteric texts), would future generations be able to reconstitute and find anything meaningful in these 78 images? Would this deck still offer something capable of informing our thoughts and actions?

It turns out that this is a valid question, for at least one person involved in the online discussion (and perhaps many others) felt that the Thoth deck is based on a specific language of symbols, defined by Crowley, such that, without his text the symbolism and the deck become meaningless. To remove Crowley, then, is to kill the Thoth deck—to make it worthless. In fact, as explained to me, symbols contain no meaning outside of the stated definitions of an individual. Strip symbols of definition and they either convey no information or they mean anything one likes.

This is absolutely contrary to the understanding of symbols held by such people as Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, the French magician, Eliphas Lévi, and countless others who have written extensively on symbolism and who believe that the meaning of the symbol is inherent in its nature. “Symbols can thus be understood as metaphors for archetypal needs and intentions or expressions of basic archetypal patterns . . . which are ultimately inherent in the human mind-brain” (Anthony Stevens, Ariadne’s Clue: A Guide to the Symbols of Humankind).

Furthermore, symbolism is a sacred, living language that reflects divinity through like vibrations. From this principle arose the occult ‘doctrine of correspondences,’ which says that something that is red, for instance, shares some kind of energy and meaning with other things that are red. Thorns that pierce are the protective weapons and barriers to the alluring rose whose scent also draws the bees. Even an esoteric interpretation takes such elements into account.

Many spiritual teachers do not fear the subjective, for they see each person as partaking of the Divine. The esotericist Manly Palmer Hall wrote in The Secret Teaching of All Ages: “Like all other forms of symbolism, the Tarot unfailingly reflects the viewpoint of the interpreter himself. This does not detract from its value, however, for symbolism is one of the most useful instruments of instruction in the spiritual arts, because it continually draws from the subjective resources of the seeker the substance of his own erudition.”

Certainly Crowley’s erudition is great, and we benefit from the knowledge he put into the Thoth book and deck (his book is magnificient!). But, if we stop there, we have not done our own work. There may be other interpreters of the Thoth deck who can also point us down what has been called “the royal road” of Tarot. Still, eventually we must make the path our own—there’s no getting around that.

The Egyptologist, R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz in Symbol and the Symbolic tells us that symbols are different than an abstract alphabet in that we can reconstitute their meanings: “Any manner of writing formed by means of a conventional alphabetical, arbitrary system can, over time, be lost and become incomprehensible. On the other hand, the use of images as signs for the expression of thought [hieroglyphics] leaves the meaning of this writing, five or six thousand years old, as clear and accessible as it was the day it was carved in the stone.” In The Temple in Man, Schwaller de Lubicz talks about the living quality of the symbol that can not survive too rigid of a definition: “To explain a symbol is to kill it; it is to take it only for its appearance; it is to avoid listening to it. By definition, the symbol is magic, it evokes the form bound in the spell of matter. To evoke is not to imagine. It is to live, live the form.” (See Schwaller’s Egyptianized Tarot Trumps here.)

Most of all I appeal to Oswald Wirth who created the first truly esoteric Tarot deck (1889; revised in 1926) that is a significant influence behind all that have followed. Wirth, in Le Symbolisme Hermétique (translated by P. D. Ouspensky), wrote that symbols are meant to awaken us to our own freedom:

“Each thinker has the right to discover in the symbol a new meaning corresponding to the

logic of his own conceptions. As a matter of fact, symbols are precisely intended to awaken ideas sleeping in our consciousness. They arouse a thought by means of suggestion and thus cause the truth which lies hidden in the depths of our spirit to reveal itself. . . . They especially elude minds which . . . base their reasoning only on inert scientific and dogmatic formulae. The practical utility of these formulae cannot be contested, but from the philosophical point of view they represent only frozen thought, artifically limited, made immovable to such an extent, that it seems dead in comparison with the living thought, indefinite, complex and mobile, which is reflected in symbols. . . . By their very nature the symbols must remain elastic, vague and ambiguous, like the sayings of an oracle. Their role is to unveil mysteries, leaving the mind all its freedom.”

“. . . Leaving the mind all its freedom.” It saddens me that the fears and anger provoked by Angeles Arrien’s book indicate a deep mistrust that the Thoth deck can survive the common touch of the “masses,” or that it has any worth whatsoever outside of Crowley’s text. It is felt that the mistakes and misconceptions in Arrien’s book (of which there admittedly are many) could create a devastating sense of betrayal in those who eventually find out that Crowley intended something different. This supposedly-fearful juxtaposition, however, led me to a much deeper appreciation of Crowley, while Angie encouraged independence and freedom in how I work with the deck and its symbols (not a good thing to those who see Crowley as the absolute and only fundament).

Although Crowley professed love for “the scarlet woman,” yet he feared the prostituting of his work, insisting that the deck and book always be sold together (it isn’t) and describing the deck’s potential use in fortune-telling as being a base and dishonest purpose (here -see text at the end). In fact, it seems that Crowley feared even the thought that anyone might claim independent insight into his deck for, despite her working diligently for five years with him to produce the deck, Crowley made clear that his student and artist, Frieda Harris, at no time contributed “a single idea of any kind to any card, and she is in fact almost as ignorant of the Tarot and its true meaning and use as when she began.” What hope is there, then, for the rest of us?

But, hope does exists, for the ever-contradictory Aleister Crowley (using the pseudonym “Soror I.W.E.“) wrote in his introductory biographical note to the Book of Thoth, that “the accompanying booklet [this book] was dashed off by Aleister Crowley, without help from parents. Its perusal may be omitted with advantage.“ If Crowley was of two-minds about how necessary his own book was to the deck, then is it at all surprising that we should be, too? I think most of us can agree that Frieda Harris’ innovative use of Steinerian ‘Synthetic Projective Geometry,’ described here, which was not in any way Crowley’s contribution, certainly deepens the effect of the deck’s imagery on the psyche.

I can only hope that, if you care about the Thoth deck, that each of you are brave enough to make up your own minds and feel free to “do as you will.” I leave you with this thought from old Aleister:

Know Naught!

All ways are lawful to innocence.

Pure folly is the key to initiation.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

47 comments

Comments feed for this article

May 7, 2008 at 1:45 am

Patricia (a/k/a Roswila)

Thank you so much for this discussion not only of The Thoth deck symbolism, but symbolism as a whole. I find this issue of there having to be one true “meaning” for any one symbol a response that I deal with in sharing or teaching poetry, too.

For me (at least as I’ve come to relate to this so far in my life) it comes down to: if there is only one meaning it is a *sign,* like the figure on a DO NOT CROSS sign at street corners. A sign does not resonate, it just stands there, static. (Although, I could imagine a poet doing things with a DO NOT CROSS sign in a poem. :-D)

But *symbols* resonate and reverberate and connect and overflow. My sense is that they have such deep roots they cannot help but speak of many things to many different people.

Yet the vessel a symbol is maintains a particular shape. It is that shape I think that may be the one true “meaning.” Maybe the esoteric understandings of The Thoth deck come from the particular shapes of the symbols. And the associative, resonant experiences of The Thoth deck symbols (such as the ones I tend to receive in Tarot readings, though I also find the esoteric ones popping up, too) come via the roots of the symbols.

May 7, 2008 at 2:56 am

Freesparrow

In my relatively short Tarot ‘career’ I have used the Thoth images for personal reflection and meditation, rarely for tarot readings. I haven’t been prepared to make the time to study Crowley in depth, although I have been curious about his system. Oddly enough I did buy Arriens’ book years ago to help with study of the Thoth but have not used that either.

I think that individuals can use images and decks in which ever way has meaning. For instance, I know an excellent reader who has used the Haindl for years without ever having read one book on Tarot. I do know people who use the Marseille as spurs to intuition with no references to underlying systems.

I tend to agree with you about symbols. I think that people do have the capacity to discern the meaning of symbols for themselves and that developing a language of symbols and meaning is a life-long journey.

But if I was to use the Thoth regularly I would read Crowley as I have read what I could by and about Waite. I’ve also done considerable work on Marseille patterns. I must say, I’ve tended to discourage people who want to use the transfer RWS generic meanings to the Marseille. In Tarot I think it is worth finding out about the intent and philosophy of the deck’s creator/s as far as is possible, even if one later chooses to use very personal interpretations of the work.

May 7, 2008 at 8:31 am

frank hall

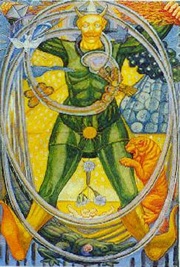

Thanks for a reasonable explanation of Angeles Arrien’s original interpretive approach. Both the “collective unconscious” and kabbalah have their validities when approaching esoteric symbolic systems. The Oswald Wirth quotation is deeply insightful about how human beings can cultivate their Self -reliant responses to symbols and find Freedom . However, to dispense with Crowley’s Vision of his own co-creation altogether seems misguided and risks skirting surfaces rather than plumbing depths. Synthesis freely unfolding might be the healthy Way — not Arrien or Crowley but Arrien and Crowley and Banzhoff and you and me and Thoth . Alchemy, not over-concentration. Consider the Thoth Fortune Arcanum — it’s a crystal with many faces.

May 7, 2008 at 9:37 am

marygreer

Thank you all for your comments. Symbols are so rich – how can they not be explored from as many different perspectives as possible? We are lucky to live at a time when so many resources are available to allow us to form a healthy synthesis. Crowley’s Book of Thoth is one of the books that are well worth rereading every couple of years – for each time you will find things you never saw before. For me, Angie’s perspective stretches the container and keeps me from getting too rigid. Plus, certain of her phrases stick with me and are so right-on in readings. For instance, I love that she sees the Queen of Swords as “the mask cutter” (even though it is a severed head that is depicted) – because it reminds me that the ideal Queen of Swords cuts through all the crap to reveal the true face of things – even when it hurts her.

May 8, 2008 at 7:06 pm

Torbjörn

I agree with you. And I feel sad when I look at the extremes in this ever-occuring debate about the Thoth. While some are afraid of Crowley, and want to avoid even the mention ing of his name, others are afraid of all attempts to interpret Crowley, and the Thoth, a bit differently than normally is done…

Too sad. Because Crowley is a rich source for inspiration. And so is Arrien!

/Torbjörn, Ligator

May 14, 2008 at 5:38 am

BMS

When I decided to start studying tarot, I went to Amazon to see what’s available. Since I was a bit familiar with Crowley – and I liked his images – I went with that deck. Based on Amazon reviews, I chose Arrien’s book to go with it.

Her book was a great introduction to the deck and it helped me begin to understand this complex, multi-layered deck. It was a great eye-opener that made me more curious about the deck. With time, I came to regard it as a bit too superficial and fluffy to continue to use it… but a great stepping stone nonetheless.

When I finally got to Crowley’s Book of Thoth, I made it to the Naples Arrangement (for those who never bothered, it means “not very far”) when I realized two things:

1. It’s a work of genius,

2. I’m not ready for it.

I had to wait until Duquette’s guidebook to dare to open that book again.

So my final verdict – both Arrien and Crowley have their good points. If I laid my hands on the Book of Thoth first, I would have given up altogether. Also, to those who don’t care for occult attributions, Arrien has everything you need to understand Crowley Thoth.

As a side note, there’s a brilliant book about Crowley Thoth and I’d even go so far to say it’s second only to the Book of Thoth in covering the deck. It’s a hefty practical manual called “Keys to the Arcana” by Maja Mandic. It is unfortunately only available in Serbian.

This was an excellent article.

May 14, 2008 at 5:52 am

marygreer

BMS – Thank you for your comment. Your experience is exactly what I’m talking about. I don’t know of anyone who has ever been hurt by The Tarot Handbook, except to the extent that they may feel misled by some faulty history and where Arrien saw an image as something different then what Crowley and Harris intended. The classic example is that Arrien says the pelican on the Empress card as a swan and so misses out on its true mythological significance. Reading both books simultaneously can help clear up such issues.

September 26, 2008 at 6:13 am

layla

BMS – My actual work with Thoth cards is mainly based on brillant manual “Keys to the Arcana” by Maja Mandic. The last info I heard was that this book was going to be translated in English. It would be really usuful for many Tarot lovers, specially her deep analysis of colours in Thoth deck, meditation work on Arcanas and complete 12 month system of individual work with Tarot.

September 26, 2008 at 9:23 am

mkg

BMS & Layla – I look forward to reading the book by Maja Mandic. Please see if you can find out who the English publisher is. I’d like to review it.

October 1, 2008 at 12:15 am

MMM

MMM – The book Kays of Arcana by Maja Mandic is translating on english and available like e-book on http://books4allof.us/ss.

October 1, 2008 at 12:18 am

MMM

MMM – Corect adress

http://books4allof.us/ssl/product_info.php?products_id=85&osCsid=2456dfee402572e8e4db2880021f6d51

October 1, 2008 at 6:29 pm

mkg

MMM – I’ve heard this is an excellent book and I’m sure lots of people will be delighted that it’s finally available in English.

If anyone gets the book by Maja Mandic please give us a report here.

October 11, 2008 at 2:13 pm

Richard Davis McLeod

Angles Arrien was one of the presenters and co-ordinators at the first Tarot Conference I ever attended at the Unitarian Church in San Francisco, I think in either 1983, 84, or 85……..my the years start running together! Anyway, I have wondered whatever happened to her, as I never hear her name anymore and she was not at the last conference I attended in San Francisco 3 years back. Could someone out there let me know the current whereabouts and circumstances of Angeles Arrien? thanks, Richard

October 11, 2008 at 2:27 pm

mkg

Richard –

She still works out of Sausalito. You can find her schedule and information at:

http://www.angelesarrien.com/

I saw her last year and she was doing great. She now focuses primarily on her Four-Fold Way and Second Half of Life teachings and is still a professor at a couple of colleges in the Bay Area.

November 24, 2008 at 2:21 am

Thomas Schwarze

On the question if we can safely separate the Crowlean references and explanations of symbolism from the Thoth deck:

Allow me to cite from another “authority” in esoteric and occult matters: Dion Fortune (Violet Fioth), once a member of the Golden Dawn off-shoot Stella Matutina, states in her excellent standard textbook “The Mystical Qabalah”:

>> These strange old charts could be handed on from generation to generation, their explanation being communicated verbally, and the

true interpretation would never be lost. When in doubt as to the explanation of some abstruse point, reference would be made to the sacred glyph, and meditation thereon would unfold what generations of meditation had ensouled therein.

It is well known to mystics that if a man meditates upon a symbol around which certain ideas have been associated by past meditation, he will obtain access to those ideas, even if the glyph has never been elucidated to him by those who have received the oral tradition “by mouth to ear.” <<

(end of quote)

Source: Dion Fortune, The Mystical Qabalah (first chapter)

Even though Mrs. Fortune speaks about the Qabalah, I think the same holds true if we apply these thoughts to the Thoth deck: after all, the symbolism of the Thoth deck is based on the Tree of Life of Qabalah as taught in the Golden Dawn.

It is still used around the world in various schools and /or esoteric groups for meditation and teaching the hidden meanings of unseen microcosmic and macroscosmic forces, so we will find a rich storehouse from which to draw our personal insights into the meaning of each card.

So let´s go and kick out that old drug addict´s personal visions:

the Tarot is far older and has survived the most hilarious variations in design and definition. It will also survive even if we kill the Thoth deck; and still be able to convey the deep mysteries lieing concealed in the 78 visual representations of cosmic Forces.

Just my two cents,

Th. Schwarze

Berlin; Germany

April 5, 2009 at 12:23 pm

mkg

Thomas –

Excellent explanation. Thank you for the quote from Dion Fortune.

It can be valuable to follow a teacher precisely, until you’ve learned what you need to learn from that teacher, but usually there is a time to let go and let the work teach you directly. And, there are always individuals who ‘intuit’ the teachings from the beginning. There are many paths . . .

Mary

April 20, 2009 at 12:42 am

stellaire

Dear Mary,

I agree with your lastest comment about learning torot. May I use it in my article on my blog? I will show your name and blog in my article.

April 20, 2009 at 12:50 am

mkg

stellaire –

I’m delighted to have you put my article on your blog. Thanks for asking. It looks like it is in Japanese – is it?

Mary

April 20, 2009 at 4:51 pm

stellaire

No, It is in Chinese. I am in Taiwan.

Thank you for allowing me to use your comments.

October 7, 2009 at 10:23 am

Robert E. Graham

I work with the Crowley deck. I find it to be brutally honest in readings.

A bookseller friend of mine said the “Crowley Deck will never lie to you.” To me the tarot has a life of it’s own. I consider the cards to be living beings and they sometimes say things I’d never get from the symbolism. For instance the “Nine of Swords” insists HE doe not deserve his reputation. HE insists you need a sense of humor to understand him. Follow the symbolism and you have a hard time getting a positive meaning from the “Nine of Swords.” I find I get hints from the most unusual places. For instance the History Channel did a show on knieves and blades. They make the comment that you can carve a roast with a knife but, a sword has only on purpose.

Robert E. Graham.

February 9, 2010 at 3:12 pm

Thoth Tarot Back in Print | Metaphysical News shop EyeofHorus.biz Metaphysical Books Psychic Readings

[…] Greer has a wonderful take on the symbolism of the Thoth, and symbolism in general in her article, Killing the Thoth Deck, she explores the power of the images and the difficulty some people have in learning the Thoth […]

May 12, 2010 at 5:17 pm

YzYgY

Well, I’ve come a long way in my own understanding of Crowley’s Tarot since learning how partitioning the deck by digital root is the Key to its decryption; and, in that respect, we owe a debt of gratitude to Arrien and the ‘constellations’ printed in her Tarot Handbook. As I recall, her introduction cited their origin as having resulted from a prolonged ecstatic trance during which she came to understand what Lady Harris meant by the trumps being pieces that, according to their own law of order, moved across a checkered board within a celestial game of chess.

On a hunch 1 thouht 1 theses constellation spreads might offer some insight on the emanation of number through the Qabalah Tree. And while it is most certainly that, they were also a means to comprehending a most ancient secret long hidden in plain sight.

Just don’t forget the VITRIOL.

And I think it was in contrast to these methods of using the Book of Thoth that Crowley probably considered gambling or fortune-telling a prostitution of the Tarot. Definitely open to interpretation, yes, but ultimately a mnemonic TOOL for unlocking the Hermetic arts & approaching the mysteries contained therein.

To Meta Therion certainly knew more than he let on; so his book, like Fortune’s, only alludes to paths the adept must walk for them self – and in that sense may be omitted with benefit. Though I highly recommend them both.

May 12, 2010 at 6:01 pm

mkg

YzYgY –

Crowley’s QABALAH OF NINE CHAMBERS (LIBER CCXXXI) divides the Hebrew Letters and thus the Trumps into the same nine constellations or “chambers” as did Arrien except that Crowley put the Fool (Aleph) with the Hermit and Moon (Yod & Quof).

The following is directly from Crowley:

Units are divine — The upright Triangle.

Tens reflected — The averse Triangle.

Hundreds equilibrated — The Hexagram their combination.

1. “Light.” —[Here can be no evil.]

Aleph The hidden light—the “wisdom of God foolishness with men.

Yod The Adept bearing Light.

Qof The Light in darkness and illusion. [Khephra about to rise.]

2. “Action.” —

Bet Active and Passive — dual current, etc. — the Alternating Forces in Harmony.

Koph The Contending Forces — fluctuation of earth-life.

Resh The Twins embracing — eventual glory of harmonised life under Sun.

3. “The Way.” — [Here also no evil.]

Gemel The Higher Self.

Lamed The severe discipline of the Path.

Shin The judgment and resurrection [0 Degree=0Square and 5 Degree=6Square rituals.]

4. “Life.” —

Dalet The Mother of god. Aima.

Mem The Son Slain.

Taw The Bride.

5. “Force” (Purification). —

Heh The Supernal Sulphur purifying by fire.

Nun The Infernal Water Scorpio purifying by putrefaction.

This work is not complete; therefore is there no equilibration.

6. “Harmony.” —

Vau The Reconciler [Vau of Yod-Heh-Vau-Heh] above.

Samekh The Reconciler below [lion and eagle, etc.].

This work also unfinished.

7. “Birth.” —

Zain The Powers of Spiritual Regeneration.

The Z.A.M. as Osiris risen between Isis and Nephthys. The path of Gemel, Diana, above his head.]

Ayin The gross powers of generation.

8. “Rule.” —

Chet The Orderly Ruling of diverse forces.

Peh The Ruin of the Unbalanced Forces.

9. “Stability.” —

Tet The Force that represses evil.

Tzaddi The Force that restores the world ruined by evil.

May 13, 2010 at 6:37 pm

YzYgY

There is also a vague reference to the arabic modification of root’s mnemonic value in his chapter: “What is Qabalah?” included in 777. Yet in neither work does Crowley apply the Tarot enumeration to the Hebrew alphabet, adhering instead to values given the letters in gematria. While the subject never fails to stir up controversy, the Tarot de Marseilles pattern does function as a cipher for accessing the Hermetic knowledge encrypted within the sequence and structure of the Hebrew alphabet.

Fitting Arrien’s constellations together upon the Qabalah Tree to assemble the Caduceus requires the Tarot ranking of letters: 0-21. This provides a means to understanding both our journey through the Tree & the ancient mystery schools’/Pythagoras’ integration of arithmetic, geometry, music & astronomy into a coherent model of the Cosmos. It is strange that, for all their intellectual rigor, the majority of Tarot historians appear both unfamiliar with & unwilling to learn this method of understanding why Antoine Court de Gebèlin claimed an Egyptian origin. In fact, the subject tends to evoke an eerie silence among Taro-philes & Qabalists alike. Hmmmm.

Of course, there may be commercial &/or proprietary imperatives for downplaying these alchemical applications of the deck…

Nonetheless, the ‘hidden stone’ definitely qualifies as the greatest punch line in the history of the world.

😉

11 / 14

14 / 11

√3 = 30˚N

May 13, 2010 at 6:56 pm

mkg

YzYgY – The fact is that dozens of systems for the tarot have been proposed based on rational justifications for their significance that fail to convince a majority of others. if you follow the lead of Le Monde Primitif then Aleph is the World card, Bet is Judgment and the letters follow the trumps in this reverse order.

There is, in fact, no silence around De Gébelin’s claim for an Egyptian origin. Most early books repeated this theory without any supporting evidence and a whole series of tarot decks are based on it (see the Schwaller de Lubicz Tarot Deck). It would gain more credibility if the trump images were grouped together anywhere in Egypt (see my post on Egypt & Tarot).

May 14, 2010 at 12:01 pm

YzYgY

Soundly based in the mathematics of acoustic geometry, the application of Tarot to the Hebrew alphabet (aleph=0) reveals “a work of the former Egyptians, one of their books that escaped the flames that devoured their superb libraries, and which contains their purest doctrines on interesting subjects.” The assertion has nothing to do with the literal translation of ‘egyptian’ hieroglyphs as, having been derived from them, the symbols attributed the Hebrew letters were once depicted by those hieroglyphs. Considered with their attribution to elements (mothers), planets (doubles) and zodiac (singles), partitioning the deck by digital root fits them together to form the components of a Caduceus. With respect to how the symbols of Tarot map onto the Qabalah Tree in order to represent this process, One could say the 10 sephiroth and 22 pathways of the Tree of Life are a kind of game board, and the numerology of the Tarot deck is used to gather the game pieces.

One versed in the alchemical allegories attending the Great Work will then see the iconography of the deck fall right into place – especially as concerns the purification of Gold ore through the use of antimony.

Technically, neither de Gebèlin, nor Crowley ever broke their oaths of secrecy concerning the proper application of the cypher. The Fool ushers in what ultimately leads to a prank. of sorts; but is himself a pun on the use of Zero (from the arabic word: sifr), placed at both beginning and end in this cycle of major ‘secrets’ (arcana).

Although it is true there are dozens of systems presented with Tarot, the evolution of the Milan pattern: from Viscounti-Sforza to Tarot de Marseilles to Book of Thoth – bears the imprint of an aenigma that has been the philosopher’s riddle for ages. It evokes an eerie silence because those who know of what I speak do not wish to spoil the riddle; nor the ‘punch-line.’ And, given the subject matter, until One actually ‘sees’ the hidden stone for themselves, the whole contraption just sounds… foolish. But, to a Freemason delving in studies of ancient symbolism, at a time when the doctrine of prisca sapientia was held by leading thinkers of mathematical & metrological inquiry, it is not too extreme to suppose that Court de Gébelin, the Comte de Mellet and their peers might have known about this connection between Tarot and the Great Pyramid’s location:proportions. A fraternal brotherhood deeply interested in the secrets of the master builders would have found it rather hard to miss.

231 : 343 : 127

Personally, I don’t like to see the riddle spoiled either. It’s an aptitude test and an inside joke that’s been around for a very long time. And a pretty good One at that. But I question whether the tradition of secrecy attending this System is truly warranted; and, perhaps foolishly, I hope making it more accessible will go a ‘bit’ further toward opening our Eye.

XX

(Φ)

XII

May 14, 2010 at 1:01 pm

mkg

YzYgY –

I have a policy that my personal blog is not a place for others to grandstand their own agendas nor to harangue others about their unwillingness to learn what you claim to know but won’t tell. Please, keep your secrets to yourself. Taunting people with their failure to solve some secret “aptitude test” is not acceptable. I will remove all further communications along this line.

Start your own blog or write a book to promote your message. Don’t do it here.

Mary

June 7, 2010 at 1:00 pm

Barbara Klaser

It does seem he was full of contradictions, being such a rebel himself, and a visionary, but denying the possibility that anyone else should be the same in regard to his deck.

I tend to think of the collective unconscious as the same thing as the Akashic Records and the Book of Thoth that Crowley claimed to be the depository of wisdom, so I fail to see anyone’s problem with someone accessing that wisdom independently, through their own filter. Of course there are pitfalls in doing so. I’m sure Crowley came up against those himself, and Jung and others have pointed out the need to avoid confusing the ego with other aspects of our psyches or the collective unconscious.

But for anyone to tell me, as if I were an errant child, that no, I must access this through Crowley, is absurd.

I haven’t read Arrien’s book though, so I can’t comment on it. Thanks for an insightful blog entry, as usual. 🙂

August 10, 2010 at 10:27 pm

Zyphir

Thanks so much for your insight and dedication.

June 29, 2011 at 4:30 am

Uri Raz

There’s a bigger question / disagreement whether the meaning of a work of art (painting, poem, book, etc) is whatever the artist intended it to mean, or what the viewer finds in it, e.g. see Authorial intent in wikipedia.

Angeles Arrien takes, at least in this case, the position that rejects the author’s intentions. She’s entitled, and as she clearly states so in the book she wrote, I have no issues whatsoever with her position and book.

What I find wrong is that some people teach what’s written in her book as The One Truth, which applies not only to the Thoth deck, but to other decks as well, e.g. the Waite-Smith deck.

[Just to be on the clear side, I take it to be a fault with those teachers, not Angeles Arrien – she was clear on this point.]

June 29, 2011 at 12:03 pm

mkg

Uri –

I agree that the Authorial Intent article at wikipedia is well-worth reading. As an English major, I started out with the New Criticism, got interested in the Jungian and Campbell approach, and then became fascinated with a biographical and sociological approach. So, I find them all valuable for really understanding a text.

With the Thoth and other decks we often have several overlapping view points – that of the conceptualizer, the artist, other commentators/teachers, and the user. To think that any one of these is “The One Truth” is probably the biggest fallacy of all. If a basic premise is that symbols transcend the individual, and their meaning can be discerned separately from any text, then we are all free to interpret them for ourselves. OTOH, some people have a certain talent, if not genius, for understanding symbols. Also, a commentator can introduce us to a perspective and related information that we might not have discovered on our own.

I can’t help but see it as unnecessarily limiting when, in order for one’s own perspective or teacher to be right, all others have to be, as if by definition, wrong.

I find that I use a blend of Angie Arrien, Hajo Banzahf, and Crowley (with notes by DuQuette, et al), and that the more I read other people, the more I go back to Crowley with a renewed respect that I don’t think I would have developed as much if I hadn’t read other views. That being said, there are a couple of commentators whose ideas about the Thoth deck make no sense to me at all or are so watered down as to be essentially meaningless. But, that’s my opinion.

April 17, 2013 at 10:16 am

James Wells

Thank you for this, Mary. I appreciate when a “both-and” mentality enters the room rather than a “versus” mentality. Imagine sticking only to Arthur Edward Waite’s texts when using the RWS deck; we’d never get any meaning pertinent to the early 21st century. For some reason, something that Jung supposedly said comes to mind: “Thank god that I am Jung and not a Jungian.” i.e. the followers of any particular school of thought so often take things so literally and get stuck in a bit of a time warp. I salute Aleister Crowley’s creative powers and his willingnss to dive into consciousnss deeply AND I enjoy when fresh, mythological, psychological, cross-cultural references come into using the Thoth deck. After all, we do live in an age where that sort of coming together of cultures is happening.

November 2, 2015 at 4:42 pm

andrea siebert

I was so delighted by this conversation. As a teacher or personal creative process, I am dedicated to the subjective as our own basis of happy and wise life gestures. That the Tarot, in all its permutations, is sought out and “danced with” in so many ways shows us how potent our inner cosmology is.

The inclusive approach I find here is, I notice in my practice, most useful to the evolution of our souls, or individual potential. I will be grateful to receive e-mails alerting me to more commentary on this wonderful subject.

November 3, 2015 at 5:00 pm

mkg

Andrea – It is difficult for some to accept that there is more than one valid approach to reading the Tarot. Luckily people will do whatever people want to do regarding this. Personally I’ve found a study of the Tarot traditions and meanings to be extremely helpful as they get me out of the ruts of my own thinking and help me be more objective about the message in the cards.

Mary

December 14, 2015 at 1:39 pm

Djamila

Just found this article and it is music to my ears. I was quite recently almost burnt at the (online) stake when I expressed the fact somewhere I started reading Thoth without ever having touched a book or webpage written about this deck, let alone Crowley’s own teachings. And that I was still reading it like that, having fallen in love with the deck. For some reason I wanted to do it differently and see how far the *true* symbolism of the art would get me, by just working on my subconscious. Not being ‘hindered’ by book studies. Much to my initial surprise and disbelief of others (“AC was a genius, you CAN’T read Thoth without his work”) I got immediate ‘hits’ and accurate and very deep readings/answers. Most of those answers were actually quite close to those who have studied the books or works of AC and some were new. I am thinking I won’t be touching that material any time soon, because I am having way too much fun with the art-work. Obviously it has complete strength all on his own.

December 15, 2015 at 1:48 pm

mkg

Djamila – Many people use Tarot psychically – as triggers to their own psychic abilities. Others have more of an “oracular” experience with the cards, which may involve a personal approach to the symbols. Others like having the structure of a system or working with the intent of the creator of the deck. When it comes to doing readings it is more about the skill of the reader than about which of the methods above are emphasized. However, if you’ve developed a personal understanding of the cards then don’t expect the readers of the other methods to be able to validate your experience. A group discussing Crowley’s Thoth deck will want to have a common ground and there may not be any common ground between your experience and theirs. Only a rare, few exceptional people are able to sway others to a seemingly iconoclastic perspective.

Mary

August 12, 2016 at 5:33 pm

Djamila

Mary, I -unfortunately -missed your response and ended up here again by searching for something else. Taking the opportunity now.

I understand what you mean. Back then I wasn’t expecting any validation on the way that I read it, but I was rather surprised that in an open discussion group (so a group where all decks can be discussed, not necessarily just Crowley’s Thoth deck) I was so cornered for having started to read the deck without any prior knowledge of GD-teachings. As if I was committing blasphemy. Moreover, after some time I realized (and expressed) the fact that many of my personal understandings were very much in line with the system others rely on – that common ground if you will. To me that emphasized that in many cases symbolism is so strong or perhaps in this case Frieda Harris was so well instructed that AC’s message reached me without having to read his Book of Thoth. I was hoping to show those feeling overwhelmed and intimidated by Crowley’s Thoth (in most cases after they read one page in Book of Thoth, because they are focused too much on the back story of the creator or because so many swear it can only be read after extensive studying), that there are solutions of creating a bond with the deck before you start hitting the esoteric books.

Perhaps in stating this I am actually countering Arrien’s vision.. I don’t know. I haven’t read her work (yet). I am happy I took the iconoclastic route for a while (and sometimes still do). It opened me up in different ways as a reader, combining analytics from said systems and that oracular experience). But I won’t fool myself into thinking I am one of those exceptional people convincing others to do the same.

Thank you for a wonderful blog!

August 14, 2016 at 4:48 pm

andrea siebert

I love how the subjective within each of us devises conscious creative acts this blog demonstrates such devotion to personal power Glad I found you all.

March 4, 2017 at 3:09 pm

jessie essex

Reblogged this on jessie essex and commented:

Interpretation if fluid might have an infinite number of perspectives, as long as what is revealed contains wisdom, then the art is living and the symbols will stand the test of time.

January 23, 2018 at 1:20 am

Alan Tate

I feel this is a misunderstanding resulting from a shallow understanding of Jung. Jung states that Archetypal symbols have a specific sort of meaning. But the meaning can never be pinned down and can mean many different things at once. However, ideas can be added onto archetypes and this is where you are correct in saying that an understanding of these symbols would require knowing crowleys own individual thoughts. But until an idea is added onto a symbol it essentially means the same sort of thing to most people. Symbolic meaning can change over time because the collective unconscious is not fixed so if thelema, for instance, were a staple of culture for thousands of years than crowleys own meanings for symbols could become fixed in the collective unconscious. This and the fact that you misunderstand what a symbol is and what a sign is as defined by jung. According to how jung defines symbols, many of crowleys “symbols” are simply signs pointing to already established ideas of his. A symbol is something unknown. Now crowley may link a symbol through his own ideas, to another set of ideas or symbols but this is just a new interpretation that is not currently at the time of its creation simething universal but something personal. Read jung thoroughly and this article doesnt make sense in my opinion. An archetpe could be say encountered in dreams and what im saying is that until an idea has enough pull over enough people to make it have an effect on the collective than it is not something univeral but personal. Christianity added to many older symbols new interpretations which over time have added to the older archetypal meanings to create an expanded archetype. But even then it cant be proven that some ultimate archetpe is simply not just becoming more and more conscious by humanity over a long period of time. Its all just a matter of how you are viewing what an archetpe is and where its energy comes from and if it has some sort of “goal” or through necessity will unfold into its highest possible understanding in human consciousness. Jung is also working as a scientist and so has to beat at and chisel his ideas into a scientifically acceptable hypothesis

January 23, 2018 at 12:13 pm

mkg

Alan,

The point is, are knowing Crowley’s “signs” essential to reading the Thoth deck or can the Thoth deck be read as symbols in a way that is meaningful and helpful to the person? And, are the archetypal images in the deck enough to evoke similar “meanings” in individuals over decades or even centuries such that the core meanings of the cards can be rediscovered even without Crowley’s text? Are Crowley’s works essential to someone wanting to use the deck? By example, if all books on the Marseille trumps or Rider-Waite deck were destroyed but people knew they could be used for divination, could new books be written that would give similar meanings to the cards as those we now know?

Although your discussion of symbols is fine and Jungians often reference the ‘unknown’ aspect of symbols—they are not just that or else one could not amplify their meanings through an understanding of myth and cultural meanings. I think you’ve overly reduced Crowley’s own ideas as “signs” rather than his choosing them because they would trigger more archetypal emotional and cognitive responses in the viewer. Certainly he includes personally meaningful ‘signs’, but rarely does such an image not also have broader cultural significance of which he was also aware.

Thanks for taking the time to read this carefully and comment. I appreciate your clarifications.

Mary

April 25, 2018 at 12:16 pm

Aeon

I’ve been looking for “Keys to the Arcana” by Maja Mandic and saw someone mentioned it in the comment thread here, albeit ten years ago. I can’t seem to find an english version of it anywhere, for sale or otherwise, and am wondering if anyone here has a copy of it. It would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.

May 18, 2019 at 6:57 am

Marilyn from Tarot Clarity

Thank you for this article.

It made me think of a parallel example; while looking at TdM art, and the historic Italian decks before them, upon which all decks owe acknowledgment, who knows every story behind every card’s origins of imagery?

We might loosely understand references to Madame Fortune, the Black Plague, and The Last Judgment, but we can only guess at the pedigree of the Popess in example. Still, that does not preclude us from interpreting her image when we see it, nor should we be denied the right to experience what she has to offer.

Crawley stressed that Lady Harris contributed nothing to the meaning of the cards, but she still had the last word on the cards in much the same way that PCS did. Crawley was unable to bring his vision into view, if he could have we’d be looking at his art and not hers. At the very least, she interpreted his vision in the way SHE understood it.

If his book were to be lost to time, but Harris’ art were to survive, It would be read in the same way that we continue to read the TdM or any art whose story is dependent on what is represented.

Crawley’s admonishments were ego driven. I have a strong distaste for his words and behavior, but Lady Harris’ art is compelling and manages to transcend it.

May 18, 2019 at 2:35 pm

Mary K. Greer

Marilyn,

Yes, does a deck stand on its own? Or can it? Certainly Crowley’s book adds to an appreciation of the deck and of the Golden Dawn tarot tradition, but is it essential? You make some very good points. Thank you.

Mary

May 18, 2019 at 3:39 pm

Marilyn from Tarot Clarity

Thank you for the courtesy of a reply Ms Greer. I appreciate it.

February 7, 2021 at 1:57 am

Mary Adams

hermeneutical mysticism’…[is] a disciplined practice of reading, writing and interpreting through which intellectuals actually come to experience the religious dimensions of the texts they study, dimensions that somehow crystallize or linguistically embody the forms of consciousness of their original authors. In effect, a kind of initiatory transmission sometimes occurs between the subject and object of study…’ Jeffrey Kripal

I am reminded of this point whenever I look at debates surrounding these type of subjects. I knew people who met Crowley and there is no consensus on the man or his work. Having known others like him from an era before occult practices became widespread, it might be said that though some of them were not always like able as personalities, it did not mitigate the truth of what they had observed about their subject or human nature. The simple fact is that they had a role to play, often contentious, but from which others were able, in part, to define themselves by experiencing that shadow.

It is said the earth plane is the only place where opposites can meet, and therefore provides us with a rich learning experience, not found elsewhere. Yet, the path we seek, emotionally at least, is usually to reconcile or integrate those experiences or personalities into something we can understand and tolerate, usually from a higher viewpoint. Yet, often much depends on out early learning experiences, giving rise to subtle emotional preferences. For me, the Raider-Waite tarot is still the one that I remember most of all and resonate to, because of my early experiences. Mouni Sadhu’s book on the tarot is full of gentle memories of places I once walked. It is not to say they they are better or worse, or that one is not aware of the limitations they may reveal over time. But, they are significant because they permit me to access distinct personal experiences which can be accessed silently upon my silent path. We must each use the tools we have been given to unlock what is within us, whether or not it may unlock for another.

March 16, 2021 at 3:08 pm

Mary Greer

Mary Adams,

These are such wise words. It makes sense that Earth is the place where opposites can meet in that duality is an obvious theme with a sun and moon of the same size, plus day/night being matched by the turning points of the Solstices and predominance of two sexes. I like the idea of this being the place where we meet in order to understand those opposite poles.

Mary