After exploring five hundred years of the moralization of playing cards in Part 1 and Part 2, we finally get to playing cards and, eventually, tarot, as a book of wisdom. I included this section under the theme of “moralization” because it shows a development of this theme into social-spiritual-political reform and a shift from an orthodox Christianity to a Humanism that arose in the Renaissance and Enlightenment. We see here that playing cards (and/or tarot) have been viewed, on occasion, as a book of the wise, teaching a timeless philosophy leading to the betterment of humankind. I’d like to preface this section with a reminder of the origins of the occult tarot.

Radical Social Reform and the Hieroglyphs of the Wise

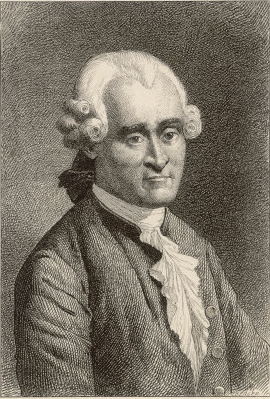

In 1781 Antoine Court de Gébelin (actually Antoine Court, from Gébelin), son of a famous Huguenot pastor, published an essay in his encyclopedic work, Le Monde Primitif, in which he declared the tarot came from Egypt and was related to the Hebrew letters. The text of Court’s essay and an accompanying one by Le Comte de M[ellet] has elements that suggest that these ideas about tarot did not originate with them, but were possibly based on materials available in French Masonic lodges (to which Etteilla also belonged). The early-19th century magician Eliphas Lévi hints at this:

In 1781 Antoine Court de Gébelin (actually Antoine Court, from Gébelin), son of a famous Huguenot pastor, published an essay in his encyclopedic work, Le Monde Primitif, in which he declared the tarot came from Egypt and was related to the Hebrew letters. The text of Court’s essay and an accompanying one by Le Comte de M[ellet] has elements that suggest that these ideas about tarot did not originate with them, but were possibly based on materials available in French Masonic lodges (to which Etteilla also belonged). The early-19th century magician Eliphas Lévi hints at this:

“The true initiates, contemporaries of Etteilla, the Rosicrucians, for example, and the Martinists, who were in possession of the real Tarot . . . were far from protesting against the errors of Etteilla, and left him to re-veil, not reveal, the arcanum of the veritable claviculae of Solomon.” (Lévi, Mysteries of Magic, p. 270)

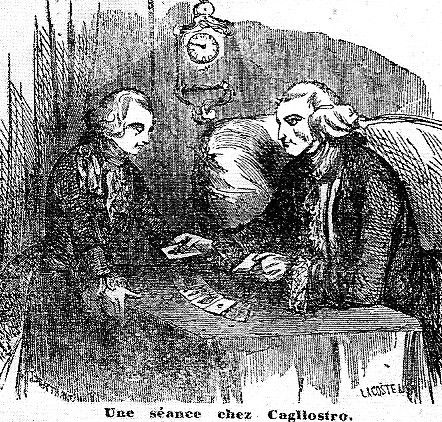

The fact that Egypt is given as the source of the tarot was not unexpected, because Court’s encyclopedia was an allegorical examination of ancient mythologies (which he believed began in agriculture). This led to a search for the origin of language and the remnants of original hieroglyphs that he saw as containing the symbolic and mystical knowledge of the wise. He attempted to catalog the universal mother tongue and grammar by deciphering all traces of the primal language still extant in the modern world. The tarot was, to his mind, one of these hieroglyphic languages. A powerful advocate of radical social reform, including freedom of religion and of independence in America, Court believed that reconstructing this proto-language would bring about social-regeneration through “a single grammar of physics and morality,” allowing “modern men nothing less than a chance to uncover the timeless, natural laws governing human happiness, and thereby to restore peace and prosperity on earth” (see Rosenfeld). In addition to the Masonic lodge of Les Neuf Sœurs (“Nine Sisters”), which he co-founded, Court was a prominent member of the Order of Philalethes (founded 1773), who, as scholarly ‘Searchers of Truth,’ were on a mission to track down everything that could be found on the occult sciences in Freemasonry. Another member was Cagliostro, famous for his institution of an Egyptian Rite in French Freemasonry. I’ve not found any written reference to Cagliostro and tarot, but he gained his reputation, in part, as a successful fortune-teller and was depicted in the following illustration as a cartomancer.  Antoine Court de Gébelin was not the first to envision such a socio-political regeneration in which the tarot cards would play at least an oblique part.

Antoine Court de Gébelin was not the first to envision such a socio-political regeneration in which the tarot cards would play at least an oblique part.

The Italian Connection & The New-Found Politicke

In 1612, an Italian who reported on (and satirized) the political, moral and literary issues of the day and advocated religious tolerance, Trajano Boccalini (1556 –1613) published in Milan, I Raggvagli di Parnasso (“Advertisements from Parnassus;” also De Ragguagli di Parnaso, see article by Andrea Vitali, in which he asserts that the game played was probably with ordinary playing cards, not tarot). Parnassus was the mountain of poets, an equivalent to the Olympus of the gods. First printed in Milan, the work was frequently translated and republished—first in England by John Florio and others who called it The New-Found Politicke (1626). It contained a chapter on cards, possibly tarot, although Vitali (above) identifies them as regular playing cards.

John Florio was born in England to an Italian father who had fled the persecution of the Waldenses in Florence. Florio was raised in both cultures, translating Italian ideas for English usage.  Shakespeare’s reference to the card game of Triumph in Antony and Cleopatra is believed to have been inspired by Florio’s Second Frutes of 1591, whose Italian proverbs and figures of speech had a great influence on the literature of the period (or Shakespeare may even have been Florio, according to Jorge Louis Borges).

Shakespeare’s reference to the card game of Triumph in Antony and Cleopatra is believed to have been inspired by Florio’s Second Frutes of 1591, whose Italian proverbs and figures of speech had a great influence on the literature of the period (or Shakespeare may even have been Florio, according to Jorge Louis Borges).

“Wrap Excellencie up never so much,

In Hierogliphicques, Ciphers, Caracters,

And let her speake never so strange a speech,

Her Genius yet findes apt discipherers.”

It was in Florio’s Italian-English dictionary of 1598 that the English learned that Tarocchi are “a kind of playing cards used in Italy, called terrestrial triumphs” and that taroccare means “to play at Tarocchi”; also “to play the froward gull or peevish ninnie” (that is, “to play the contrary fool or whining simpleton”). Frances Yates theorized in her book John Florio: the Life of an Italian in Shakespeare’s England (1934) that Florio acted as intermediary between Shakespeare and Giordano Bruno with his neoplatonic hermeticism. Florio worked under the patronage of the Earl of Southampton who was also Shakespeare’s patron and was under the patronage of both Archbishop Cranmer and Sir William Cecil—in whose house he lived for some time. These were both close friends of Hugh Latimer (see Part 1)—small world!

Getting back to Boccalini’s I Raggvagli di Parnasso (from the translation by Henry Cary, 1669): We find in the “2nd Advertisement” a short text from the start of a large work that might be thought to contain material that will inform the whole. It follows the same initial plot as the “Soldier’s Prayerbook” (see Part II) in which a young rapscallion is discovered with cards, taken before an authority to explain himself, at which time the deep mysteries of the cards are revealed, although in this case, it is the authority, Apollo, who discerns them. He explains that the game of Trumps (see Part 1) teaches hidden secrets and ‘a science necessary for all men to learn,’ a ‘true Court-Philosophy’ in that even the most worthless trump takes all the ‘beautiful figures.’ Later we will see that, to the masses, even the least-of-trifles trumps all the great wisdom of the sages. It is a satiric commentary that masks a deeper philosophy, just as to more modern tarot commentators, the triviality of tarot as a gambling game was believed to hide its higher truths.

The usual Guard of Parnassus having taken a Poetaster*, who had been banished [from] Parnassus, upon pain of death, found a paire of cards in his pocket; which when Apollo saw, he gave order that he should read the Game of Trump in the publick Schools [my italics].

*Poetaster, like rhymester or versifier, is a contemptuous name often applied to bad or inferior poets. Specifically, poetaster has implications of unwarranted pretentions to artistic value.

[The text concludes with:] Apollo asked this man, what game he used to play most at? Who answering, Trump, Apollo commanded him to play at it; which when he had done, Apollo penetrating into the deep mysteries thereof, cryed out, that the Game of Trump, was the true Court-Philosophy; a science necessary for all men to learn, who would not live blockishly. And appearing much displeased at the affront done this man, he first honoured him with the name of Vertuoso; and then causing him to be set at liberty, he commanded the Beadles, that the next morning a particular College should be opened, where with the salary of 500 crowns a year, for the general good, this rare man might read the most excellent Game of Trump; and commanded upon great penalty, that the Platonicks, Peripateticks, and all other the Moral Philosophers, and Vertuosi of Parnassus, should learn so requisite a science; and that they might not forget it, he ordered them to study that game one hour every day; and thought the more learned sort thought it very strange that is should be possible to gather anything that was advantagous for the life of man, from a base game, used only in ale-houses; yet knowing that his Majesty did never command anything which made not for the bettering of his Vertuosi, they so willingly obeyed him, as that school was much frequented. But when the Learned found out the deep mysteries, the hidden secrets, and the admirable cunning of the excellent Game of Trump, they extolled his Majestie’s judgement, even to the eighth heaven, celebrating and magnifying everywhere, that neither Philosophy, nor Poetry, nor Astrologie, nor any of the other most esteemed sciences, but only the miraculous Game of Trump, did teach (and more particularly, such as had business in Court) the most important secret, that even the least Trump, did take all the best Coat-Cards” [“che ogni cartaccia di Trionfo piglia tutte le più belle figure”].

The Rosicrucians and a Universal Reformation of the World

Meanwhile, in Kassel, Germany a revolutionary paper with far-reaching consequences was being written by a young Johann Valentin Andreae and friends who were part of a utopian brotherhood. The supposedly anonymous Fama Fraternitatis or Rosicrucian Manifesto was published in 1614 and had an impact that no one could have imagined. It tells the story of Christian Rosenkreutz who traveled to the Middle East where he met sages and mystics, learning from them esoteric wisdom and knowledge before returning to Europe where he founded the secret Brotherhood of the Rose Cross (the Rosicrucians). This secret order consists of men, dedicated to the well-being of humankind, who travel the world healing and teaching. It gives an account of their discovery of the hidden tomb of Rosenkreutz, whose body lies, in centre of the vault, perfectly preserved after the passing of over a century.

The Fama first appeared with a preface: “Advertisement 77” of Boccalini’s just published I Raggvagli di Parnasso that called for a “Universal Reformation of the World.” Although it doesn’t mention cards directly, we saw that an earlier chapter did. Its purpose regarding the Fama has been much debated because the follies of these reformers of the world are openly ridiculed. “Advertisement 77” depicts a fraternity of the world’s wisest men who debate many ideas about how to resolve the world’s conflicts. Despite their belief in the high principles of love and caritas, they conclude that the masses will always prefer relief of their immediate problems over the true reform of society. And so they lower the prices of essential foods—to great rejoicing—rather than enacting the lofty reforms they had just discussed. Boccalini despairs, not believing that intellectual enlightenment will prevail. As A. E. Waite describes it:

“They fixt the prices of sprats, cabbages, and pumpkins . . . for the rabble are satisfied with trifles, while men of judgment know that—as long as there be men there will be vices—that men live on earth not indeed well, but as little ill as they may, and that the height of human wisdom lies in the discretion to be content with leaving the world as they found it.” (Waite, The Real History of the Rosicrucians, 1887.)

One modern Freemason believes that Boccalini’s satire was making it “clear that the first step for the reformation of the world must necessarily be the reformation of the spirit.” Frances Yates suggests that the inclusion of Boccalini may, in part, have been an oblique reference to Giordano Bruno and certain “secret mystical, philosophical, and anti-Hapsburg currents of Italian origin.” She explains,

“Giordano Bruno as he wandered through Europe had preached an approaching general reformation of the world, based on return to the ‘Egyptian’ religion taught in the Hermetic treatises, a religion which was to transcend religious differences through love and magic, which was to be based on a new vision of nature achieved through Hermetic contemplative exercises.” [Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 136.]

Others claim there is an alchemical interpretation for the text. Manly Palmer Hall attributes Boccalini’s chapter to Lord Verulam, Francis Bacon, known as ‘the Chancellor of Parnassus’ (his wife was a huge Bacon fan).

The Wise Men of Fez

Now, Paul Foster Case (who created the BOTA tarot) was well aware of the first edition of the Fama Fraternitatis, having written his own book on the Rosicrucian Manifesto. I also believe he was familiar with the whole Ragguagli as he seems to have blended Advertisements 2 and 77 into his tale of the origin of the tarot. According to Rosicrucian legend, Christian Rosenkreutz studied in Egypt and at length arrived in Fez, the holy city of Morocco that was, during the Middle Ages, one of the most famous centers of the alchemical arts. In The True and Invisible Rosicrucian Order, Case sets his own mythical origin of the tarot in Fez and places the wisdom of all the gathered sages into a deck of cards, whose pictures speak a thousand words, equally in all languages. He clearly wants his readers to believe that the tarot was one of the “many books and pictures sent forth” by the Rosicrucian Fraternity that could speak in many languages of their treasures: the secrets of spiritual alchemy that could bring about “general reformation both of divine and human things.” And, as Waite commented above, “as long as there be men there will be vices,” so that wisdom imparted through a tool of gambling would never be lost.

The Rosicrucians Come to France

Let us return now to France, where some believe that (in contrast to other European nations) Rosicrucianism failed to take hold. But, several scholars have noted that in 1623 a mysterious placard was affixed to the walls of Paris:

“We, the deputies of our chief college of the Brethren of the Rosy Cross, now sojourning, visible and invisible, in this town, do teach, in the name of the Most High, towards whom the hearts of the Sages turn, every science, without either books, symbols, or signs, and we speak the language of the country in which we tarry, that we may extricate our fellow-men from error and destruction.”

On the 23rd June 1623, “A general assembly of Rosicrucians was reported to have been held in Lyons” (G. Naudé, Instruction à la France sur la verité de l’histoire des Freres de la Roze-Croix, 1623, p. 31). A Rosicrucian lodge of Aureae Crucis Fraternitatis was founded in 1624. (Jean-Pascal Ruggiu, Rosicrucian Alchemy and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn). By the late l8th century, the Order of Philalethes and some other Masonic lodges had instituted Rosicrucian grades.

Pure Speculation

There are few factual historical connections among all this material. Yet there seems to be a functional connection in which the deck of cards serves as a hidden reminder, manifesting through time in a variety of forms, of moral truths and spiritual teachings. Could explorations of the sources of the Rosicrucian Manifesto by the Order of Philalethes have turned up Boccalini’s entire Raggvagli with its chapter on the Trumps? Might the Italian Cagliostro have included tarot when he was teaching his Egyptian Rite to French Masons? Hopefully, this new information should excite speculation, perhaps bring to light some overlooked facts, and encourage us to explore questions about the role of cards as carriers of ideas in human culture and philosophy.

Le Grandprêtre Tarot

Were these cards created to illustrate the text of Antoine Court de Gébelin or did they inspire his text?

The cards in this deck, from the John Omwake Playing Card Collection, have many of the same titles that appear in Le Monde Primitif. They were attributed by Catherine Hargrave in A History of Playing Cards (1930) to early 18th century France. Stuart Kaplan in his Encyclopedia of Tarot, V.1 dates them 1720, but in V.2 he changes that to late 18th century, post-Le Monde Primitif (p. 336-7). Other than this deck, the first use of the terms High Priest and High Priestess (Grandprêtre and Grandprêtresse) instead of the Pope and Popess are in LMP.

The cards are 1-7/8″x3-3/8″ and were, according to Hargrave, made from copper plates and then hand-colored, so they must have had some distribution. There is no separate Fool card, but he appears in place of the Devil on card XV.

If influenced by Antoine Court why aren’t his card descriptions followed more closely? Could the originally estimated date possibly be correct?

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

13 comments

Comments feed for this article

February 12, 2011 at 4:09 am

Paul Gipp

Thanks Mary! One of the best blogs on Tarot history I’ve seen in some time. I have a theory of a “Collective Effort”, in terms of the Tarot being compiled as a communication and educational tool in Renaissance Italy. This material will help greatly in my continuing research into my speculations.

February 12, 2011 at 8:16 am

Gidget London

Fabulous reading with my coffee this morning. What a great piece to wake up to!

Truly wonderful.

Thank you Mary for all of your work in research and writing Tarot to SHARE with us!

Gidget

February 12, 2011 at 1:29 pm

Christine Payne-Towler

So excellent Mary! It’s a pleasure to see this and the other two articles in this series. I keep thinking that the more we look into the Lodges and Orders, the more we will see the “hidden history” of Tarot that’s been missing from the public record. Tarot’s profile in the secular, public mind is only part of the story.

February 12, 2011 at 2:25 pm

mkg

Christine –

How good to hear from you. I thought of you several times as I was writing this piece. I must admit that there are few direct connections in any of this, but it’s more than we had before. Partly, I find the social reformation theme to be of great interest. As characteristic of the Enlightenment, we move away from traditional Christian moralization into Humanism.

February 12, 2011 at 3:48 pm

Daniel

What you compose for a blog post most people submit for a Master’s Thesis! I am thrilled with this work – I plan on following sources this evening and getting deeper into the material. I had frequently heard that Tarot descended from the Egyptians – but never saw any credible sources showing that in any non Lexus Dixit manner (a because-I-said-so type of fallacy.)

Looking forward to P-con coming up and more enlightening lecture from you.

February 12, 2011 at 4:14 pm

mkg

Thank you, Daniel. I’m sure I’ll keep coming up with modifications and changes as people inform me of my errors. I do this because it’s fun.

Yep, and I have to get busy preparing for PantheaCon!

February 12, 2011 at 7:44 pm

david vine

Mary,

Wonderful, wonderful, wonderful! Just a slight tweak, though: It is de Mellet who connects the Trumps with the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, not de Gébelin. De G. observes in passing that the Hebrew alphabet, like the “Egyptian alphabet” consists of 22 letters, but does not connect the Hebrew directly with the Trumps. I have just completed new translations into English of both articles from “Le monde primitif…” (which people should know, is not so much the “primitive world” as the “primeval world”). When all are ready, the de G. and de M. translations will be accompanied by translated texts from Eteilla and other 19th-cen. French cartomancers. I am hoping at last to make these works, fully accessible, in good, reliable language, to the English-speaking tarot world. Keep your fingers crossed!––David V.

February 12, 2011 at 8:57 pm

mkg

David –

Actually I phrased my statement so as not to make CdG the assigner of correspondences like de Mellet (associating Aleph with the World, etc.). I didn’t want to get into the particulars, but I’m glad you brought it up here.

I did my own translation of the two essays several years ago (with help from a friend), which I’m sure has plenty of errors, but I haven’t put it on my blog. I generally send people to Donald Tyson’s page (but it might be down now). I don’t know enough to know what is the best translation so it will be interesting to compare. As far as I know there is practically nothing directly from Etteilla. I look forward to seeing what you have learned from him. Also, the cartomancy texts are of great interest to me.

February 13, 2011 at 5:21 am

david vine

Oh, Goddess! I just hate sounding like a prig about these things. Mr Tyson’s translation, unfortunately, is full of hundreds of misunderstandings and mistakes. I know nothing of his translator’s credentials, but just to demonstrate it is not merely a matter of sloppy verb tenses… For example, in a complaint about the debased state to which he believes fortune-telling (“a science so sublime”) has come in his day, de Mellet asserts it has been reduced to “l’usage des enfans de tirer à la belle-lettre”. Tyson has this as “the practice of children to draw the beautiful letter”. The correct translation, which involves an old French idiom of which Tyson must have been unaware is “the childish custom of inserting a pin among the pages of book to select one at random” (like the old Bible roulette). This material is so important to us and so fascinating on its own, it ought to be done right. The cartomancy texts are exhilarating. I am being inspired at every turn!

February 13, 2011 at 5:39 am

david vine

… and, oops! I meant to apologize about the Hebrew letters. Sorry! I do see what you are saying. I had an underground motive, though. 🙂 Working with this material so closely has made me a mite sensitive to the casually dismissive tone I have come across in not a few tarot writers (not you, certainly!) when it comes to these guys. Specifically, it is disappointing that (a) so many detractors focus on the “ridiculous” connection of the Trumps to the Hebrew letters or, more frequently, the “Egyptian problem” which, prior to Champollion’s deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, strikes me as a perfectly reasonable, even intelligent, guess; and (b) that these men, who could and did read Latin, Greek, Italian, Spanish, German and more, and whose frequent perceptive citations from classical and medieval authors and texts back up what they say at almost every turn, should be described as “dilettantes” and “pseudo-scholars” (by the likes of Theodore Roszak, e.g.) who didn’t know what they were talking about. Take a breath, David. Take a breath.

February 13, 2011 at 9:54 am

mkg

David –

I figured that some of the idioms were getting past me and even Donald Tyson. I’m so glad you are doing this translation. It’s exactly what we need. I have a special request for your next project. Please do Paul Marteau’s seminal work on the Marseille deck. I’ve had several French translators look at it and groan, saying his language is almost impossible to translate. Maybe we’ve just been waiting for you.

I’m so glad to hear you speaking up for Court de Gébelin, et al. The more that I get a glimpse into his environment and larger concerns, the more the whole thing starts to make sense to a ‘history of ideas.’

February 26, 2011 at 4:49 am

Mary K. Greer: Moralization of the Deck of Cards, Part 3 | Tarotpuu

[…] https://marygreer.wordpress.com/2011/02/11/moralization-of-the-deck-of-cards-part-3/ […]

March 2, 2011 at 7:51 am

Sharyn

thank you for sharing your research and knowledge so freely.

Sharyn